History

SARDINIA’S MEDIEVAL KINGDOMS: THE JUDICATES

Although researchers suggest that their institution dates to the Byzantine period, the origin of the Judicates is still uncertain. Later, the four judicates would have become four independent kingdoms.

More...

Judicates’ society, politics and donnos (10th-13th century)

In the late Middle Ages, the Judicates of Cagliari, Arborea, Torres and Gallura tightened their friendship and alliance with the powerful and invading communes of Pisa and Genoa, to be progressively dispossessed of the territorial power, with the only exception of the Judicate of Arborea.

The judge had control over the state lands (called rennu in the local language), which were often granted to relatives or fellow nobles with the secatura de rennu formula (part of the state domain). In fulfilling his mandate, and especially in the exercise of his jurisdiction, the judge was assisted by the Corona de Logu, formed by the maiorales.

The curatores were responsible for the government of the territory; they were officers who chaired over the curatorias, the administrative subdivisions of the Judicates. Along with the curators, the maiores de scolca, were responsible of the smaller portions of the territory called scolcas, sometimes including three or four small villages. Later, maiores de scolca were replaced by the maiores de villa.

The political-administrative structure of the Judicates reflects a society strongly marked by the land power of the donnos, a noble elite that owed its wealth to the ownership and management of large farms, where their servants used to work. The donnos aristocracy was partly a secular and partly an ecclesiastical élite, with origins as uncertain as the judges; it is likely that their foundation dates to the Byzantine period, when it was responsible for military and civil offices, which were later passed on through to the judicates. Some of these élite families, such as the de Athen, the de Serra, the de Thori, could possess thousands of hectares and were almost always related to the houses of the judges, whose common ancestors seem to be the Lacon-Gunale family.

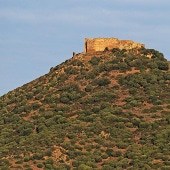

The Church also had great land possessions, especially including farms linked to convents and abbeys. Between Uras and Masullas, the remains of the important Vallombrosian abbey of St. Michael of Thamis can still be found.

under the aragon monarchs

Following the decline of the Judicates and the arrival of the Catalan-Aragons’ monarchs, the map of jurisdictional and land powers underwent a full redesign due to the feudalizations.

More...

Sardinian aristocracy under the Aragon’s Crown (14th-15th century)

To take possession of the Kingdom of Sardinia, the Aragons’ sovereigns granted dozens of fiefs to those who actually participated in and/or funded military expeditions.

These grants were made secundum mos Italiae: following the death of the concessionaire, their fief returned into the hands of the sovereign. In those years, the most influential feudal families were mainly military families: Boixadors, Oulemar, De Llors, Ballester, Carroç. Amongst them, there were also some Sardinian families, such as Atzeni, Gambella and Marongiu, and from the Italian peninsula, such as Doria, Malaspina and Donoratico. In 1355, the convening of Parliament by Peter IV the Ceremonious legitimized the new Sardinian-Catalan aristocracy. The transition between the old Sardinian, Pisan and Genoese elite, with that of Catalan, Aragon and Valencian origin was robust but not radical.

After the successful battles of Sanluri in 1409, against the last judge of Arborea Viscount of Narbonne, and of Macomer in 1478, against the last rebel and Marquis of Oristano Leonardo Alagon, the Kingdom of Sardinia finally passed under the control of the Iberian sovereigns, and became part of the confederation of the Spanish kingdoms since 1479.

At the end of the 15th century, two trends emerged: on the one hand, the pressure by Sardinian feudality to consolidate the parliament, in order to obtain greater privileges and noble titles; on the other hand, a process that lead to the control of almost half of the Sardinian territory in the hands of three great feudal lords (the Duke of Mandas, the Count of Quirra and the Count of Oliva). However, these feudal lords preferred to settle in the Iberian territory, close to the Royal Family and have their feuds administered by the podatari, designees with fully delegated functions.

the spanish DOMINATION

Under the Spanish domination, from baronies or lordships great feuds became counties and marquisates. Between the 16th and 17th centuries, the Spanish sovereigns granted a large number of noble titles, not necessarily linked to a fief.

More...

Sardinian aristocracy under the Spanish Crown (16th-17th century)

The granting of knighthood and nobility titles (often connected, but with some exceptions) had different reasons and were mainly granted for political and administrative purposes, or upon specific merits or services to the Crown.

Before the title was granted, the fulfillment of merit requisites – especially bloodline and religious faith- was assessed through an investigation. Upon its successful outcome, their investiture ceremony would occur, and the viceroy would ratify the new knight, granting them a number of privileges; with some rare exceptions, he would also grant them a coat of arms.

Knights and nobles had special fiscal and legal privileges: they could be judged only by their own social class and were subject to the jurisdiction of the General Lieutenants and the Governors.

They could seat in the Military Stamento parliament and could carry weapons with them.

Under the Spanish domination, three classes of noblemen stabilized: the feudal lords who descended from the first conquerors or feudal lords by new concession; the non-feudal nobility who accomplished public, administrative or military functions; the hereditary, noble knights, who represented the smallest class, since they only owned a single title, although it often had ancient origins.

the savoyard DOMINATION

In 1720, following the Spanish succession war and the international treaties redefining the European political situation, the Kingdom of Sardinia passed from the Spanish crown to the Savoy sovereigns.

More...

Sardinian aristocracy under the Savoys (18th-19th century)

The feudal system and ecclesiastical concessions occupied nine tenths of the island’s territory. In addition, the great feudal lords such as the Marquis of Quirra, the Marquis of Villasor and Orani, the Duke of Mandas and the Count of Oliva resided outside Sardinia, in Spain or Austria.

At the end of the Spanish period, the Iberian crown abnormally granted innumerable noble titles. Between the late 18th and the early 19th century, the Savoys started to grant countless titles and knighthoods, both to limit the powers of the previous feudal lords in the territory and to fulfil the ambitions of the local elites who demanded greater space in public jobs.

Thus, “Nobles of the Robe” were created; this new class of nobles was composed of officials and jurists who would participate in the Kingdom’s discussions over political and administrative matters.

Sardinia was also granted various knighthood and nobility titles for financial merits; this is especially the case of all the nobles appointed after the so-called Editto degli Ulivi (lit. translated: Olive Trees Act; TN) dated 1806, or those ennobled for having financially supported the construction of the road linking Cagliari and Oristano.

With the elimination of fiefs (1835-1838), the old nobility still maintained their social privileges, having a significant impact on Sardinia’s political history.

After the perfect fusion in 1847, the combined, uniquely Spanish title of Knighthood and Nobility was no longer granted; however, the titles already possessed by the families were confirmed. Thus, generic Nobility titles were granted -without Knighthood and without the title of ‘Don’- and sometimes also the titles of Count or Baron, without fiefs; however, these titles were associated with state or private lands.

POLO MUSEALE MASULLAS

More...

...allodiale, con la prerogativa di successione anche per linea femminile e l’esercizio in sede giurisdizionale del mero et mixto imperio, che concede il potere di amministrare la giustizia sia nel civile che nel criminale.In ogni curatoria o baronia appartenente al Marchesato vengono istituite le curie baronali e sono nominati i diversi giudici. Le cause sono spesso di natura fiscale, altre riguardano fatti criminali. L’amministrazione della giustizia feudale risulta però confusa e arbitraria: curie senza archivi ordinati, personale dotato di scarsa preparazione, corruzione e connivenza con i bandos organizzati, carceri ridotte al solo ceppo e in locali molto ristretti.

Masullas, oltre alle milizie, ospita in questi locali la curia baronale con le relative carceri.

Nel 1564, per fermare lo strapotere dei baroni nell’amministrazione della giustizia, il sovrano spagnolo Filippo II istituisce il tribunale della Reale Udienza, che giudica in appello sulle cause tra vassalli, villaggi e feudatari.

A farne parte sono letrados esperti in materie giuridiche. L’incarico più importante all’interno della magistratura è il Reggente della Reale Cancelleria, coadiuvato da altri giudici, come l’Avvocato Fiscale.

In seguito alla richiesta degli Stamenti nel Parlamento, nel 1651 viene istituita la Sala Criminale della Reale Udienza, con competenza sulle cause di natura penale.

Il ruolo che la Reale Udienza assume nel corso del periodo spagnolo non è meramente giuridico, poiché essa col tempo diventa un organo consiliare che supporta i viceré nel governo del Regno.

Info

Ex Convento dei Cappuccini

Via Cappuccini, 57

09090 MASULLAS (OR)

Sardegna

Italia

coopilchiostro@tiscali.it

Collegamenti

- Atti amministrativi

- Termini e condizioni

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- CEAS

Newsletter

Iscriviti alla nostra newsletter per rimanere aggiornato sugli eventi del polo museale del comune di Masullas

SOSTEGNO PUBBLICO

PROGETTO NEOLITHIC PARK 3D

CUP: E78D17000220007

Bando CultureLab “Sostegno finanziario alle imprese del settore culturale e creativo per lo sviluppo di progetti culturali innovativi”